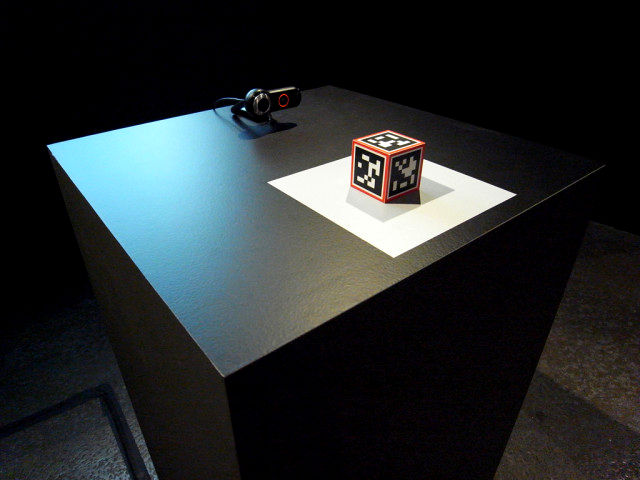

levelHead is a spatial memory game by Julian Oliver.

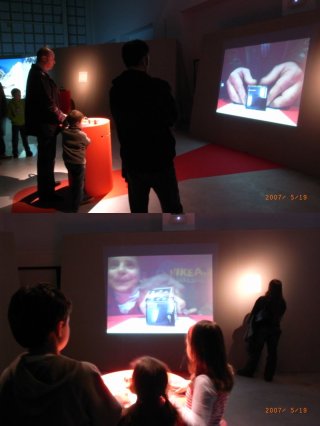

levelHead uses a hand-held solid-plastic cube as its only interface. On-screen it appears each face of the cube contains a little room, each of which are logically connected by doors.

In one of these rooms is a character. By tilting the cube the player directs this character from room to room in an effort to find the exit.

Some doors lead nowhere and will send the character back to the room they started in, a trick designed to challenge the player's spatial memory. Which doors belong to which rooms?

There are three cubes (levels) in total, each of which are connected by a single door. Players have the goal of moving the character from room to room, cube to cube in an attempt to find the final exit door of all three cubes. If this door is found the character will appear to leave the cube, walk across the table surface and vanish.. The game then begins again.

Someone once said levelHead may have something to do with a story from Borges.. For a description of the conceptual basis of this project, see below.

Demo video:

levelHead v1.0, 3 cube speed-run (spoiler!) from Julian Oliver on Vimeo.

Other videos:

Press

"While nowadays most artists generally go for full body interfaces and giant screens, Julian built a fascinating, tiny little world in a box that is a pleasure to play with. Game art doesn´t get any bigger than this."

".. my curiosity never settled as I moved my figure from room to room. I had a very real, almost God-like influence on the tiny world in my hand .."

".. if Nintendo is truly looking for new interactivity, levelHead fits the gaming giant's bill."

"Pattern recognition has already been used in several other projects, but this is a new way of using it, and a new way of thinking of the technology."

"levelHead is an Interactive BlockBusting Videogame."

"Looks like this could be the 21st century Rubik's Cube for kids worldwide, or they could look at it and think it too hard, preferring instead mind-numbing shooters like Halo 3."

"The installation [..] is totally engrossing and nerve-challenging."

Installation configuration:

Status

There is a source-code release intended for those willing to try to compile it and/or submit patches. As yet there is no binary executable available. In the meantime, levelHead is playable as an installation, appearing in several electronic arts events in 2008.

Once levelHead is more easily installable, i intend to release all levels as paper cut-outs so people can print the levels onto stiff paper, cut and fold them up to play.

It's perhaps worth mentioning that I'm currently talking with various parties about the possibility of publishing a larger and more sophisticated version of this project.

Awards

Buying levelHead

levelHead source code

Exhibitions

Past:

Present:

Future:

Galleries

Homo Ludens Ludens 20.04.08

Close up shots with paper/wood cubes

Conceptual Basis

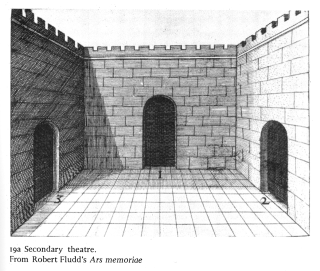

In a time without printing and paper for taking notes, these memory arts were of vital importance, both to the recollection of cultural artefacts (prose, theory, philosophical treatises) and practical tasks involving the storing of patterned information (numbers, names, dates).

Of the many earliest methods used was the construction of imaginary architectures (memory loci) that were designed to specification precisely for the purpose of storing information such that it could be retrieved by 'walking through' the building in the mind. So it follows that the relationships between objects of memory were configured as being spatially associative, with the walking imaginary self acting as a reader. This system was deployed widely resulting in memory architectures that were famously used to store and recount vast bodies of information whether that be events In a story, numbers or the names of people.

Cicero, pioneer of this technique, here describes what constitutes such a memory architecture:

We use places as wax and images as letters [...] Consequently ( in order that I may not be prolix and tedious on a subject that is well known and familiar) one must employ a large number of places which must be well lighted, clearly set out in order, at moderate intervals apart and images which are active, whch are sharply defined unusual and which have the power of speedily encountering and penetrating the mind.

Quintillian, a prominent teacher of Rhetoric in the 1st Century, Rome said of the art of memory:

I am far from denying those devices may be useful for certain purposes as for example if we have to reproduce many names of things in the order of which we heard them. Those who use such aids place the things themselves in their memory places: they put, for instance, a table in the forecourt, a platform in the atrium, and so on for the rest and then when they run through these places again they find these objects where they put them.

Today, in modern times, we enjoy the luxury of domestic printers, digital tagging systems, address books and journals (on and offline) that do the remembering for us.

Today, in modern times, we enjoy the luxury of domestic printers, digital tagging systems, address books and journals (on and offline) that do the remembering for us.

These systems have us storing what we need to remember in indexed and exterior locations like remote databases or local filesystems. As a result we find ourselves both reliant upon (and conditioned to) access information in a pointillistic, on-demand fashion.

It is the great advances in data management, database design and search engines that allow us to both store and access information in this way, by 'moving' from one location of externalised memory to the next. As such we need not know how to return, how to find our way through data as even the navigation is being managed for us, a path through the data.

So it follows that the describing of one object's structural and mnemonic relation to another is no longer a valuable part of the data itself, instead it is work done by by way of an abstracted proxy like a server, history list or state-ful file-browser.

Similarly, navigating in the real world increasingly tends toward dependence on external media and locative technologies, remembering not just places but even describing vectors of movement and spatial associations for us. It is in the spirit of Memory Loci, of the configuration of place as both an associative location and container of memories, that the design for levelHead begins. It prioritises the notion that moving from one site to another inevitably produces an imaginary architecture of varying clarity and positions this memory architecture as the primary means of navigation. Only one side of the cube will reveal a room at any given time and so a memory of the last room - of the positions of entrances and exits, stairs and other features - is necessary in order to build a logic of safe forward movement.

It is this navigable accumulation of spatial associations in memory that is configured as the core mechanism of play in levelHead. Rather than the computer containing these relationships for the player it is the memory architecture of the human player that describes the scope of their free movement. It is a game that in order to be played relies on the imaginary and unseen architecture being of equivalent relational resolution to that of the digital architecture displayed.

It is this navigable accumulation of spatial associations in memory that is configured as the core mechanism of play in levelHead. Rather than the computer containing these relationships for the player it is the memory architecture of the human player that describes the scope of their free movement. It is a game that in order to be played relies on the imaginary and unseen architecture being of equivalent relational resolution to that of the digital architecture displayed.

The tangible interface aspect becomes integral to the function of recall also: as the cube is turned by the hands in search of correctly adjoining rooms muscle-memory is engaged and, as such, aids the memory as a felt memory of patterns of turns: "that room is two turns to the left when this room is upside down".

The Rubiks cube has been described to operate in a similar fashion. This may explain the great many likenesses drawn in journals and blogs between levelHead and the Rubiks Cube.

Technical Description

Further software provides an animation management facility for the character model: by analysing tilt movements across two axes, the character can be directed to turn and walk in a given direction.

Several people have written suggesting that I make a version of levelHead with LCD

screens. Naturally this is something I did already consider. I chose not to

attempt to use screens in a hand-held cube for the following reasons:

Several people have written suggesting that I make a version of levelHead with LCD

screens. Naturally this is something I did already consider. I chose not to

attempt to use screens in a hand-held cube for the following reasons: Six 5cm LCD screens at 1cm depth each would require the cube is much bigger to accomodate the inset frames and housing. This would leave a maximum space of 6x6x6cm inside the cube to fit a >=2GHz computer with a powerful graphics card, battery, cooling fans and a 3D accelerometer (like that in the WiiMote). Such a computer does not exist currently.

Furthermore, a camera equivalent in quality to the EyeToy would need to be on each side of the cube in order to track the face of the viewer. Unless the computer can know where the eyes of the viewer are there would be no sense of being able to 'see around the corner' and therefore no illusion of the rooms being somehow inside the cube. Instead, the player would merely be turning a series of small screens in their hand, each with a 'flat' and unshifting room (ie as static as a printed image).

A solid cube, webcam and a desktop computer is a robust and elegant solution. It takes high-temperature, expensive, fragile, high-tech electronics out of the picture, leaving just a person and a solid object as the control interface.

Software used

Platform

History

While containing no game-play or avatar, Unprepared Architecture will continue to be developed as an experiment in augmenting architecture on a site-specific basis.